Another shop you don’t need to go in.

A sunny, windy Saturday morning. A queue of cars waits to turn right into a muddy field, creating a hold up on the A60. Each car is full of junk. The people from the cars unload their junk onto trestle tables and tarpaulins. People exchange items of junk and money. This is not a film crew re-making ‘Grapes of Wrath’ on location. It is a car boot sale, and it’s a tragedy.

You have a car that is 99.9% working. The part that isn’t working is a warning light that comes on when it shouldn’t. Ironically, the warning light is a faulty alarm, giving warning only of its own falsehood, but it is enough to fail the MOT test and render the car worthless.

The car must be recycled, and it is not a tragedy. Gordon Brown used to pay people to dispose of cars, successfully stimulating the Korean economy. For a while cars could be handed in for a bounty, like coyote pelts.

In our town centres, piles of junk are decanted into vacant shops under the guise of charities and sold on for slightly more than you might pay at Primark, if only you weren’t phobic and dared go in.

No disrespect to charities. It is just a pity that they have been sucked into the landfill business.

One of the best things you can do to help yourself is to throw away half your stuff. So, lots of lifestyle gurus have latched on to ‘decluttering’.

However, as Tony Blair didn’t say, its not enough just to fight clutter – we have to fight the causes of clutter also, otherwise it will merely return in a new and terrible form.

Why do we have so much tat?

The economic answer is that our society values economic growth above all other measures of civilisation.

The evolutionary answer is that for most of human existence it has really paid to hoard stuff away. Our grandparents, who lived through wars, failed to adapt to the disposable society and proved unable to dispose of their empty yogurt pots and biscuit tins. Many of them were killed in hoarded item landslides.

The psychodynamic answer is that we invest emotion in objects, so that they acquire a sentimental value. Under this heading we include whatever defence mechanism is responsible for Collecting Things.

The cognitive answer is that we hate waste. In particular we hate to lose stuff that we already have.

I don’t doubt for a moment that already there are huge land fill sites, and that a lot of land fill should really be recycled, and that land fill is problematic from an environmental point of view.

It’s just that, judging by the state of many people’s houses and sheds, the land fill sites should be so much bigger. Somewhere around the size of Bedfordshire, as a rough estimate.

Borrowing a bit from Escape from New York, why not declare an area – such as Bedfordshire – an official landfill site and build a tall fence around it? Gradually, Bedfordshire would grow taller and mountainous and probably beautiful in due course – if you could find it.

I would like to see a huge re-cycling plant for vinyl records where they can be turned into food by a special fungus.

I’d like to see all the remaining cathode ray televisions collected, melted into a giant saucepan and made into comfy chairs .

And all the books – after digitising – can be made into a new Hadrian’s bookcase along the entire Scottish border.

All the coins and money could be melted down and made into the kind of shiny foil clothing people in the 1960s imagined we would all be wearing by now.

And most of all, I’d like to see all those cardboard crowns that litter the window sills in Burger King, collected, pulped and made back into trees.

Architect and designer Mies Van der Rohe is credited with the saying ‘Less is More’. He would have been a little disappointed to find so little evidence of minimalism or even room to swing cats in our houses today. Though modernists would probably have expected people to swing their cats in verdant communal parkland between the high rise blocks, or in high quality piazza spaces, rather than indoors.

Some architects have even gone as far as to question whether cats need to be swung at all.

Digitisation seems to give us the opportunity to miniaturise the storage of all our music, video, art and documents to a card the size of a postage stamp. Using ‘the cloud’, we do not even need the little card any more.

Sadly, one has the impression that the space vacated by digitising records, books and pictures will quickly be filled by gym equipment and antiques.

It is tempting to hold the media – particularly the Sunday Times – responsible for the clutter epidemic. For instance, yesterday, the paper carried an article about buying a Victorian bidet, allegedly haunted, for £325. ‘Its sad to part with it,’ the article concluded, ‘but I’m downsizing’. What, do without a bidet! However will you manage?

In truth the blame lies closer to home. Yes, psychiatrists are to blame for the landfill explosion and thus, soon, losing one of our treasured counties. This is the reason:

Some how or other, psychiatrists have convinced the world that tidy people have something wrong with them. Tidy people are called ‘anankastic’, which sounds suspiciously like ‘antichrist’.

The word ‘anankastic’ means something similar to obsessive.

Psychiatrists have not explained very well that the anankastic personality is not the same thing at all as obsessive compulsive disorder.

Implicit in OCD is the acceptance that the thinking and behaviour is silly. Whereas the anankastic person does not think there is anything wrong with what he regards as being extremely well organised.

Psychiatrists have hinted that tidy people are repressed in some way. Something to do with anal retentiveness.

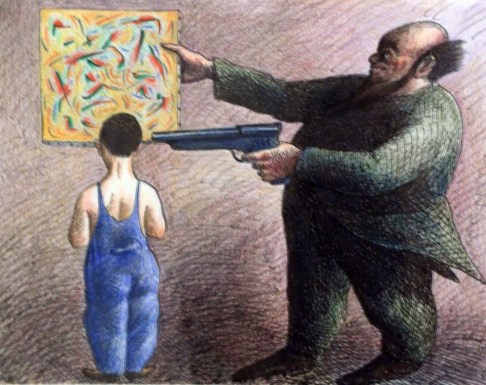

Tidy people will never be competent painters, jazz musicians or good at sex.

Look at how they are portrayed in movies and television. Radar, from Mash; Dwight, from The Office; Mr Gradgrind, from Hard Times.

Psychiatrists have been generating bad press for tidy people for over a century. There is no range of perfume called Anankast, not even in Superdrug.

There is no Anankastics charity shop in town, though by now it would have been renamed Spick and Span, to reduce stigma.

In the Mr Men series – pretty much the bible when it comes to personality classification – Mr Neat and Mr Tidy are only minor characters in the book devoted to Mr Messy.

Looking back to the late 19th / early 20th century context, when the analysts were most active, perhaps this is more understandable.

Freud and his colleagues had no PIN numbers to remember, no car insurance to renew, no DVDs to take back to the library.

They did not have to use mobile phones to pay for parking. They did not even have land lines. They had no need to keep a range of spare batteries, chargers and light bulbs, or gas cartridges for their Braun Independent beard curlers.

They had no need to use their Tesco voucher within a specific 7 day window.

Freud never had to find a 13mm ring spanner or a 30 amp fuse.

He never had to worry that Jung had hacked his facebook page.

Today’s world is so different. The need for organisation is so acute some households should think about appointing their own executive boards, complete with Venn diagrams and Mission Statements.

As a psychiatrist I feel guilty about what we have done to besmirch tidy folk, and offer the following solution:

Since we have invested a lot of emotion in objects, we cannot simply dispose of them as the de-cluttering guru suggests.

No, each item really needs a decent send- off, with a few kind words and reprisal of happy memories. This way the grief can be channelled and worked through.

The actual process would be quite like Antiques Road Show, but featuring a conveyor belt and incinerator.

That way Bedfordshire can be saved.