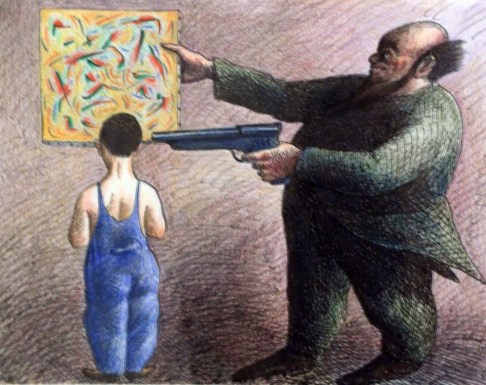

A cultural education (picture by Roland Topor)

There are several types of therapy for Depression. In one way or another they are directed at improving insight. Whether improved insight translates directly into recovery is a different matter. Also we are assuming that better insight is always a good idea. That might not suit certain vested interests and power groups who need us at the grindstone all day, in the pub all evening and shops all weekend.

There are quite a few logistical barriers to psychological treatment – finding it, getting there, sticking with it. Recently a number of computer programs, or applications, have been designed to help, with names like Beating the Blues and Fearfighter. Mostly these have been presented by IAPT therapists in health centres or GP practices. They can be accessed directly by users at a price, but its only a question of time before cheap or free apps become available for home use. These applications have been given a cautious welcome by experts such as NICE. People who are used to modern computer gaming will find them a bit pedestrian. I hope we can rely on the software industry to pump them up.

Professor Niall Ferguson recently presented an account of modern history attempting to explain the rise of western civilisation. He used the analogy of ‘Killer Apps’ to explain why certain societies had prospered.

Competition, Science, Medicine, Property Rights, Consumer Society and Work Ethic: these were the processes that had brought about Western Civilisation, he argued.

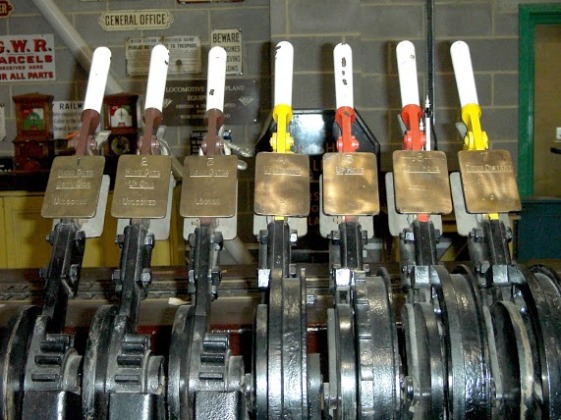

Commentators say that Ferguson has misused the term ‘killer app’, which has, or used to have, a particular meaning in the computing world, not just an analogy for ‘vital’.

A killer app was supposed to be an item of software unique to a particular piece of hardware. So if you wanted a spreadsheet or desktop publisher you had to have a Mac.

Strange that Ferguson, an academic historian, tolerated an historical inaccuracy in the use of terminology, for poetic licence. The recent history of technology is probably more interesting, important and possibly bloodthirsty than the Tudor period. Still, the killer app analogy caught people’s attention, which was probably what he intended.

History wasn’t my favourite subject at school. In fact, school utterly killed History for me; too many dates and royals. I was glad when Francis Fukuyama published his book ‘The End of History’ in 1989, though for me History ended in 1973, with the damp squib of an O Level exam. After Fukuyama published his book I fully expected all the History departments in schools and universities to shut down like the coal mines, their job finished. Instead of which we saw the emergence of Time Team and Dan Snow.

Since apps had not been invented in the 1970s, I can’t blame my History teachers for not using this illustration, though I can blame them for never using gimmicks at all. Aside, that is, from Mr Hockenhull’s epic 8mm movie, reenacting the Battle of Hastings in Disley.

Still, it’s a slippery slope between education and entertainment, one that I personally would hurtle down on a Lidl trolley, but thats another story. The trick I suppose is using colourful illustrations to explain ideas without dumbing down the key message.

I am certain that Niall Ferguson has looked at all the information available and come up with the right processes that shaped prosperity, but does it help to think of them as Apps?

Apps, on the computer at least, are processes that run within an operating system.

There are certain aspects common to any system, operating or otherwise. There’s a whole theory of systems, which spans science from engineering to economics. So there is a whole range of analogies to be made between aspects of different types of system.

So it might make sense to use the analogy of an App in terms of processes in societies, small groups of people, or individuals, all of which are systems of a kind.

A system needs to define itself using boundaries. It needs to regulate its inputs and outputs. It needs fuel broken down to provide energy. It needs feedback control to maintain itself. The same features can be found in any type of system, large or small, with the possible exception of the Beko washing machine.

Freud had a surprisingly electrical view of how the mind worked. For instance,Freud thought the mind had a range of mechanisms to protect itself from electrical overloads, which are now called defence mechanisms. For instance a murderous impulse might have its energy directly countered, or projected onto another person, or converted into a physical disorder.

Some of these defences he thought were disastrous and some more effective and healthy, such as Humour, Altruism and Anticipation. We could regard Freud’s favourite defence mechanisms as Killer Apps (almost literally) in terms of dealing with extreme thinking. In terms of treatment options, Freud had something of a killer app in the form of Hypnosis, which he abandoned in favour of the technique of free association, which is like exchanging a Macbook Air for a Babbage Engine.

Killer Apps in the Mind? After all, the mind is genuinely a computer system, unlike society, which is a mixed bag of systems, non systems and mud.

In truth, many people have attempted to explain how the mind works, using simplistic models that involve two or three main components. Analogies like these tend to break down when we try to illustrate something so complicated.

Apps however have the advantage of being highly specific. I have one that merely turns on the phone flashlight. Yet there are others that tell me exactly where I am and how to get home. I have one that tells me my car is in Munich at the moment. Inkorrekt!

Just like Prof Ferguson introduced the idea of Killer Apps to spice up a massively complicated piece about the history of the western world, we might be able to use the concept to help us talk about mental processes without being hidebound by some overarching model.

We might be able to use the App idea to spotlight certain aspects of morbid thinking.Terms proffered by CBT therapists like ‘arbitrary influence’ and ‘selective abstraction’ never felt very user friendly.

Specifically, are there certain killer apps that could protect against getting depressed, or help a depressed person, if we could only download them to someone’s mind?

Abstract thinking, such as the use of metaphor, proverbs and analogies, helps us organise information. Using templates, such as lists, mnemonics,algorithms and ‘pathological sieves’, helps organise piles of untidy thoughts.

If we could load some of that onto a smartphone we could call it something like Meta4Works or ProverbBlaster. These are perhaps part of a larger software package we could call InsightFull.

I would also like someone to invent FrameItWider and AttributeRite to counter some common cognitive errors.

Mostly we need help to make better decisions. There is a growing interest in how decision making takes place, both in individuals and organisations. Books like Nudge by Thaler and Sunstein explain how the ‘choice architecture’ affects how people behave. The role of default options is surprisingly strong.

Zhan Guo, in a paper called Mind the Map, showed recently that the London tube map affects peoples travel decisions far more than their actual experience of making journeys. Sometimes the schematic map is nowhere near to scale geographically. Instead of using the map, we could use an App, putting in the destination.

Smartphones are getting smarter and people are – in some ways – getting dumber. Think of Arithmetic and Calculators. Could we not just hand over more of our troublesome thinking to a computer? Its precisely what we have done with arithmetic after all.

Already, or pretty soon for most people, navigating a car will be delegated to a GPS system. Its a set of decisions we can safely leave to an App. Now we have a computer system called Amazon, that can tell what I want before I even know myself.

Tesco know what kind of whiskey I would buy if only I had a voucher for £5.40 off the price. Not £5.30 mind you. £5.40.

Doubtless Tesco and Amazon are using a version of choice architecture to apply nudges to my behaviour. I doubt whether they employ clairvoyants or telepaths at Tesco, so I am guessing they are using a software application which clusters together things people like me have bought. Either that or I have misinterpreted that large phone mast on Tesco’s roof and those strange headaches I am getting.

Many decisions we make, particularly purchasing whiskey, should be delegated to a wiser system. When it comes to choosing a product or service, or even the way home, there are many sources of guidance.

Sadly, when it comes to the biggest decisions of all, we are often working too quickly, without enough information, without an App at all, or with a flat battery.There is a strong relationship between poor decision making and Depression, both in terms of getting depressed in the first place, and perpetuating Depression once it has begun.

That is why the Killer App we need the most is ChoiceMaker Turbo version.

I just used it at Tesco and ignored the whiskey offer. Like their trolleys, I have a mind of my own. Also, if I’m right they will soon up their offer.

I like the analogy of Apps, but it works better to illustrate a single mental process rather than model the mind as a whole, let alone whole societies. As a way of spicing up and developing CBT for a mass market, Apps could be the way forward, but we have yet to see a Killer App for Depression. Good news for therapists who don’t like anything called a tablet. The important thing is we continue to seek better analogies all round.

As Mr Hockenhull might have said, ‘the first two periods are Biology and IT, the rest is History’.

Or, after Fukuyama, ‘home early today’.