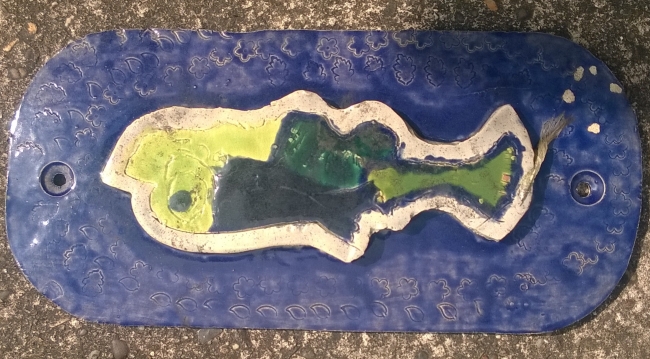

A new design to discourage revolving door admissions

If you don’t use sub-headings nowadays, people will laugh at you. Reports, for instance, need to be have all the paragraphs and lines numbered.

For the time being, everything has to be written in fives or tens. If I had to write about my recent trip to Wakefield, for instance, it would go like this:

Five brilliant things about Wakefield:

- Industry: If you buy a can of Coke anywhere across Wakefield and the north of England, the chances are it’s been manufactured using water from East Ardsley reservoir

- Talent: Ed Balls visited Wakefield College recently where he had the opportunity to speak with senior College staff and also to try his hand at bread making with a group of talented catering students.

- The Arts: Wakefield had a brilliant new art gallery called The Hepworth. It’s free but parking costs £4.50

- Celebrity: Shadow Chancellor, Ed Balls, paid a visit to HC-One’s Carr Gate Care Home in Wakefield to spend time with his godmother, who is a resident there

- Free speech: Outside the cathedral, a man is shouting loudly to himself, stating that something should be done about the smackheads.

The cathedral should be in the top 5 instead of Ed Balls, but it was closed, despite a large banner saying ‘the cathedral is open’. Smackhead trouble, I presume.

In conclusion, Wakefield just cannot be itemised. There’s a square concrete gallery full of curvy shapes, on the banks of a river that seems to be flowing in several directions at once. It’s all a bit random.

Our response to complicated questions tends to be five simple answers. For example, surveys keep revealing that there are absolutely no available mental health beds in Britain, and patients are having to be sent to the International Space Station by rocket ship, as there are still vacancies in the sick bay.

Like most other mental health news, such revelations cause no reaction whatsoever, as mass readerships turn to more interesting news within a millisecond, like Desmond Morris’s scintillating analysis of why Kelly Brook is the most attractive female, ever.

Yet, ‘on the ground’, the bed drought is massively stressful for the agencies involved, not to mention the service users and their families. What might begin as a bad hair day, muddling your tablets and starting an accidental chip pan fire, ends up as a 200 mile trip to a private sector secure unit in Yorkshire.

Why the shortage of beds?

Here are some reasons. At first glance, as often seems to happen, there are exactly five:

- The number of beds has been reduced by at least 1700 over the last 3 years

- The population has increased

- Community services have been pruned along the lines of Norman Tebbit’s rose garden in March

- Agencies are increasingly risk-averse

- The hospitals are inefficient in their workings

At least, that’s the common sense explanation, based on an analogy with any other system. This week we had floods. And overcrowding on the railways. The prisons are overflowing again. Similar reasons – simple reasons, to do with not getting quarts out of, or into, pint pots. Researchers have analysed the flow through hospitals using so called ‘stochastic’ modelling, which is derived from the mathematical properties of random events.

Once hospital departments are more than 85% full, the system jams up, just like a Dyson. Mental health acute wards are more than 100% full all the time. All the leave beds are in use and occasionally, mattresses are put down in day rooms.

But the ‘bed crisis’ is not really a simple capacity issue. Like roads – with the single exception of the M181 into Scunthorpe – and housing, there will always be excess demand. But society is quite flexible in determining which marginal group goes to which marginal venue. My impression is that there are large numbers of semi-homeless people – sofa-surfers – existing in the penumbrae between prison, hospital, homeless projects and the public library. This group meanders between the different institutions, like a shallow stream, filling any gaps it finds. Some of them fall into the police, some fall into A and E. From there, a random selection fall into the mental health system. By accident, some get into the cathedral.

Managers know there is no ‘irreducible minimum’ for mental health beds.

Managers know that beds mean hospital staff and hospital staff are a nuisance. Managers love community services, because dispersed personnel manage themselves. They seldom meet to fight or plot.

Trust managers are continuing to close mental health beds, like sheepdogs that have tasted mutton. The impact of these changes is that if you are depressed, you are extremely unlikely to get admitted to a mental health unit.

And if you do get admitted, you will very quickly decide you weren’t feeling quite so bad after all and ask for another go at community care.

Luxury items like research centres, respite care, therapeutic communities, specialist units for resistant depression, alcohol rehab, etc, are just material for Michael Gove’s new history syllabus.

Here’s the bullet point version. It turns out there are five main points:

- There’s a rising tide of homelessness

- Depressed people, for better or worse, have been displaced from the residential part of the mental health system

- People unable to manage themselves are milling about the country like fluid particles

- Put away the Airfix Kit – it’s time for Stochastic Modelling.

- If you have a cathedral, you need to check regularly for smackheads.